KUALA LUMPUR, March 7 — What do you think of when you see a museum? A place telling the history of events before you were born or of generations before you? Or a potential place for your local community — including people with dementia — to share stories together?

Here’s what Malay Mail learned during a visit to the town of St Ives in Cambridgeshire, UK, where The Norris Museum — with a collection of over 33,000 items on the local area’s history — has been engaging with people with dementia.

In an interview, the museum’s community officer Susan Bate told Malay Mail that she runs groups to bring people to the museum.

This includes hosting two reminiscence groups at the museum and conducting reminiscence sessions outside the museum. Here’s how Bate, the volunteers and the local community do it:

But first, what is dementia and reminiscing?

According to UK charity Dementia UK, symptoms of dementia can include memory problems such as being more forgetful or having difficulty retaining new or short-term information; difficulty finding the right words or engaging in conversation, losing interest to socialise, and having changes in behaviour and mood.

People with dementia could also have anxiety and depression because of the changes they are experiencing.

According to The Norris Museum’s website, reminiscing involves using objects from the past to prompt long-term memory and empower people to tell their story, with a focus on “what people can remember rather than what they cannot” remember.

It said reminiscing can help people with dementia by improving their mental health and well-being, reducing social isolation, and enabling them to form valuable connections with others.

The Norris Museum’s community officer Susan Bate told Malay Mail that reminiscing is good therapy for people with dementia. — Picture by Ida Lim

What’s in the box? Memories and free-flowing conversations

At The Norris Museum’s reminiscing sessions which have been going on for the past six years, there would usually be a box featuring different themes, such as the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, movies, fashion through the decades, and holidays.

The box could contain objects such as old photographs, newspapers from decades ago, cookbooks, shopping baskets, sewing cases, a suitcase, or clothing.

Bate said the items could be donated, purchased from charity shops, or sourced from volunteers.

To start a reminiscing session, a volunteer would pull out an object from the box to show to the group, which would then spark a conversation as people started sharing their stories.

For example, a dress might prompt someone to say their mother or sister had a similar outfit, while another might recall they wore a dress just like that on their first date with their husband, and the conversation would continue with others swapping stories on how they were not allowed to wear mini skirts when young.

“So if I started talking about a dress that’s from the 1960s, and then someone starts talking about their dress from the 1950s, and all of a sudden it moves onto wedding dresses, and then summer holidays, we just let the conversation go with what the participants want to talk about,” she said, noting that volunteers would not attempt to pull the conversation back to the initial topic but let it be led by the group.

If the conversation stops, a volunteer would then take another object out of the box and ask “Oh, what about this one?”

While reminiscing sessions are usually scheduled to last for one hour, Bate said volunteers would not stop the conversation if it goes on longer: “They just keep chatting, but we don’t have a structured session anymore. It’s just a bit more casual.”

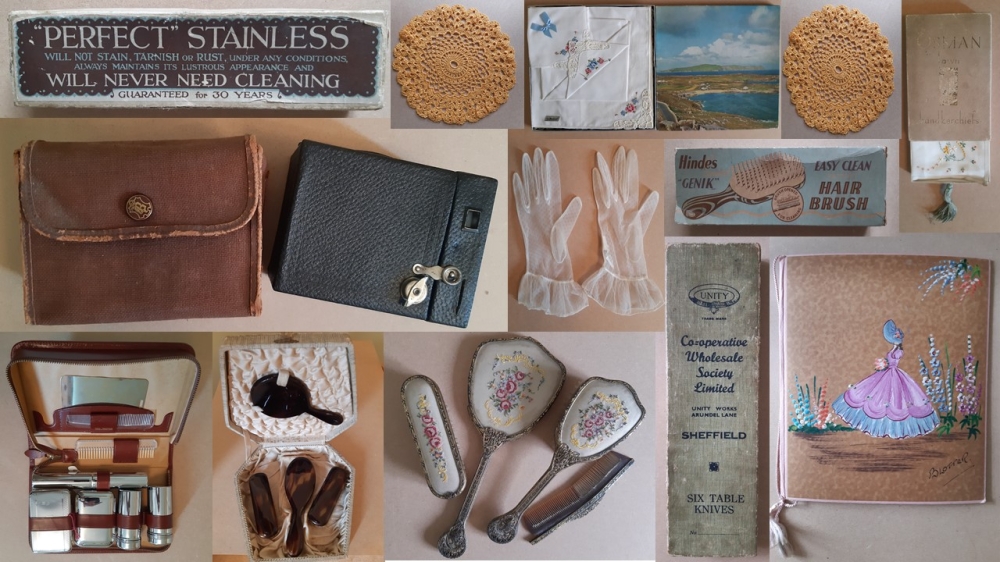

Objects that were donated to The Norris Museum for its handling collection to be used in reminiscing sessions. — Pic courtesy of The Norris Museum’s Facebook page

Having fun with history in your hands

The museum also has a “handling collection” — featuring either duplicates or non-fragile items from its main collection — that participants can handle and touch in the reminiscing sessions.

Bate said participants enjoy trying to identify such historical objects (like a 19th century pot) and work out how it was made, or what it was used for.

“I never say ‘no’ at the time that their idea was wrong. I just go ‘Is it really, could it be that? Is it? Oh, that’s interesting, oh, I’ve never heard that one before,” she said, adding that she could share some history about the object after participants tried to identify it.

At one of the reminiscing sessions, Bate asked the participants to bring an object that is important to them and to share their stories.

Don’t push if they can’t remember

Bate says reminiscing sessions can be “tricky”, with the need to avoid certain topics with some participants as they cannot remember, adding that “the worst thing for someone is that they can’t remember why they can’t remember”.

“Now it could be that they can’t remember because of their dementia, or they can’t remember because they don’t want to remember. And so it’s making sure that if someone sits there and goes ‘Oh, I can’t remember’, you don’t try and push them on the topic.

“Because obviously we block out memories for all sorts of reasons at any age, and we’re just going to make sure that if someone doesn’t want to share something or talk about something, we turn that conversation around so that they don’t feel uncomfortable,” she said.

For example, some people may want to talk about weddings as their wedding day was one of the best days in their life.

But Bate said the topic of weddings may cause others to start to think about the spouse that they had lost and that the conversation could instead be steered towards other topics like childhood memories.

“So it’s just being mindful that some people perhaps don’t want to talk, and that it’s okay not to share a memory or be part of the conversation if that’s what you feel comfortable with,” she said.

What do you remember when you see buttons, sewing, stitching and knitting tools? Shown here are objects for use in The Norris Museum’s reminiscing sessions. — Pic courtesy of The Norris Museum

What to do when sad or painful memories surface?

Bate said reminiscing can sometimes be quite challenging, as sad stories are sometimes shared during these sessions.

While saying it is natural to not want to see someone upset, Bate said: “But we know they sometimes have to go through that whole process to finish the story, that they have to be able to talk all the way through; and that we always just make sure that, you know, we’re laughing about something at the end.”

Some participants may get quite upset when talking about loved ones that have died, so efforts would be made to recall happy topics such as what they had achieved as a couple, or their children or grandchildren, she said.

Sometimes the group would have a sing-song, while sometimes the participants “might have a little hug and then they start talking about funny stories of their husbands”, she said.

“We’ve got to make sure that when we reminisce, that if something sad comes up, that we make sure we end in a happy place, that we don’t all go out the room crying because it’s been so sad, that we all end up quite jolly at the end,” she said.

Having fun at a reminiscence session by The Norris Museum, where participants often try to guess what objects are and help in the museum’s research by sharing stories of how items were used. — Pic courtesy of The Norris Museum

It’s about building a community too!

While the reminiscing sessions are intended as therapy for people with dementia, Bate said others — such as their carers, friends, neighbours or paid carers — also join in the conversation.

“But what I found is that everybody likes talking about—I’m going to say — the ‘good old days’. But everyone likes talking and sharing a story, or remembering something that perhaps they have forgotten. And however old you are, everyone reminisces,” she said.

At the reminiscing sessions, carers would often volunteer to make tea or coffee or to clear and wash things up.

While washing up, carers would have the chance to talk privately and exchange tips with each other.

Bate also said it is important to make participants feel that they are part of a community or part of a group, saying that feeling valued and involved makes them want to come back to the reminiscing sessions.

With up to 30 participants (mostly in their 70s and 80s) regularly coming to the reminiscing sessions at the museum twice a month and also other activities in town, Bate says they are “very much like a family” and would look out for one another.

If one of the regulars does not show up, the rest would ask about them and would contact them to make sure they are alright.

Susan Bate said the reminiscence group loves coming to the museum’s community room as it is relaxing and calming. Shown here is the room with a view of the river on one side. Picture by Ida Lim

Reminiscing in other settings

Bate also holds reminiscing sessions with smaller groups at care homes, where participants may be those who are at a more advanced stage of dementia.

They may stop after speaking briefly as they have forgotten where the conversation was going or what they wanted to say, or cannot think of the words they wanted to use.

Bate would then have to bring that person back into the conversation and also have to rely on the care staff there to know what may trigger the participants’ memories.

At daycare centres, those at a more advanced stage of dementia may have limits on how long they can concentrate, so the challenge would be keeping them calm and engaged during reminiscing sessions, Bate said.

A view of The Norris Museum’s garden from its community room, where reminiscing sessions and other dementia-friendly and age-friendly activities are held. — Picture by Ida Lim

Reminiscing with a shared common interest as veterans

With the help of volunteers, Bate also runs a separate monthly group at The Norris Museum known as the Royal Air Force (RAF) Reminiscence Group, which was set up about three years ago for former RAF personnel to chat about their days in service.

Mostly attended by those aged 60 and above, the group was also set up for former personnel with memory loss (such as those with dementia).

Bate said family members — such as sons and grandchildren of ex-RAF personnel who are unable to drive themselves to the museum — also take part by sharing stories they have heard while growing up.

Some ex-personnel in the early stages of dementia may get quite frustrated when they struggle to remember facts such as when they joined the RAF or where they were posted, and would need some help from their wives to prompt them on such details.

“So they bring their wife who has got a little notepad with all the key dates on, they go ‘when did I join?’ ‘You joined on this date’, and then all of a sudden the conversation starts again because he’s had that little trigger, the memories, he then remembers…then he just goes on with the conversation,” she said, adding that wives also join the conversation.

*This article is based on the author’s project during the Khazanah-Wolfson Press Fellowship 2024 at the University of Cambridge.